A few weeks ago, we published the first article of this series, in which we laid a framework with a set of criteria to meet on the roads towards becoming the Linux for MCUs.

This time, we’ll look into the first point on the list, which is the ability of being Harware Agnostic.

Hardware Agnostic, what?

Hardware Agnostic, in this context, means that software developed for a given hardware configuration may work for another one with minimal to no changes. To achieve this, the software relies on re-usable software foundation principles, which includes at a minimum:

- Well-defined APIs defined at a high, abstracting the what from the how, and being valid across all hardware variants.

- A well-defined hardware abstraction scheme, to treat hardware dependencies focalized and isolated from the remainder of the code.

Use-Case: FocusIO

To understand this in practical terms, let’s throw an example application: let’s call it, “FocusIO”.

This application uses an accelerometer-based motion detection to evaluate your ability to remain focused for long periods of time.

- The Accelerometer is phasing-out as end-of-life and the product needs updated.

- How easy is to have the codebase work with Accelerometer-C?

- Does it only require swapping the accelerometer driver?

- The very same product now also needs a microcontroller change because of chip-shortage (Let’s say this was 2020…).

- Does it only need to change the peripheral drivers to make it work?

Hardware Abstraction in Zephyr

As previously mentioned, Zephyr keeps a clear hardware abstraction by using the well-known Linux concept: The Device-Tree.

Let’s take a look at an extract of the Thingy53 device-tree source (dts) board files:

&i2c1 {

compatible = "nordic,nrf-twim";

status = "okay";

clock-frequency = <I2C_BITRATE_FAST>;

pinctrl-0 = <&i2c1_default>;

pinctrl-1 = <&i2c1_sleep>;

pinctrl-names = "default", "sleep";

bmm150: bmm150@10 {

compatible = "bosch,bmm150";

reg = <0x10>;

};

bh1749: bh1749@38 {

compatible = "rohm,bh1749";

reg = <0x38>;

int-gpios = <&gpio1 5 (GPIO_PULL_UP | GPIO_ACTIVE_LOW)>;

};

bme688: bme688@76 {

compatible = "bosch,bme680";

reg = <0x76>;

};

};In the Device-tree, we have a hierarchy outlining the board features. In this example:

- i2c1 is the main node, defining the I2C bus.

- The following fields are properties of the I2C bus (e.g: clock frequency, pins through pinctrl, etc).

- The devices that belong to the bus are defined as child nodes, each one defining their properties (e.g: 7-bit I2C address, Interrupt GPIOs, etc). On this sample: BMM150, BH1749, BME688 are the I2C-attached devices to I2C1.

At build time, the dts definition is translated into a set of applicable macro-defines as well as drivers that are selected based on the compatible property, node-label, etc. Then, the applicable drivers implement the public APIs (in this case, I2C and Sensor), which then the application uses to interface with the underlying parts of the system.

Check out this Zephyr example of the LIS2DH sensor (3-Axis accelerometer), which works on any target that has this sensor defined on its device-tree (e.g: thingy52_nrf52832, actinius_icarus, stm32f3_disco_board, among others).

MCU Support

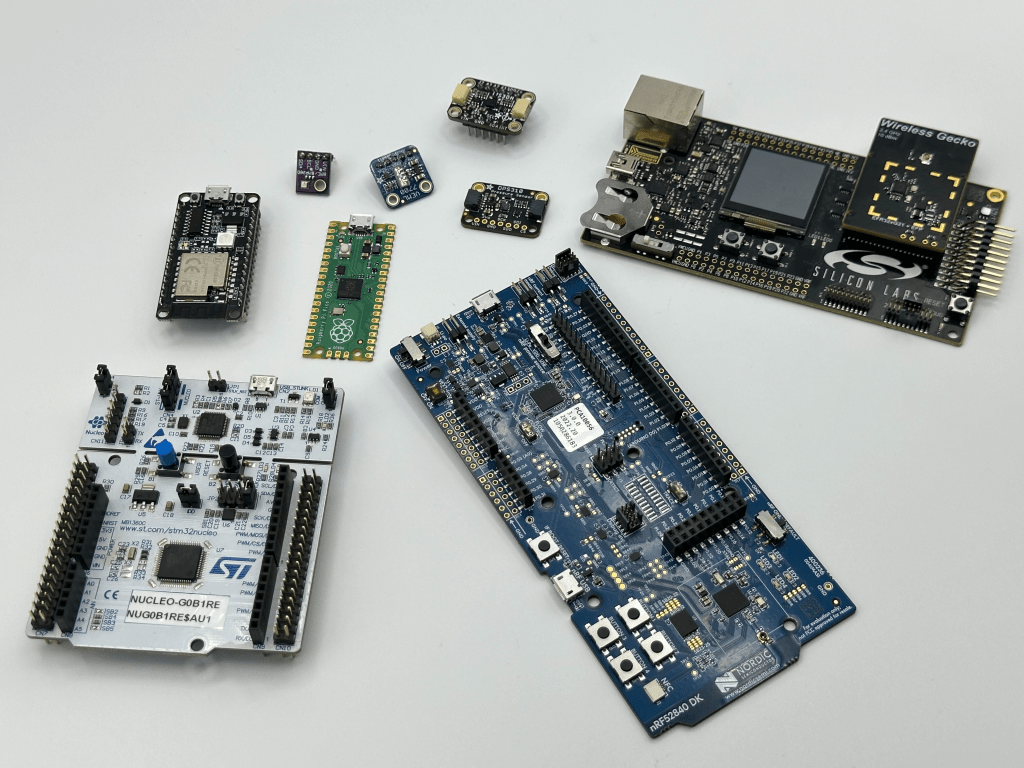

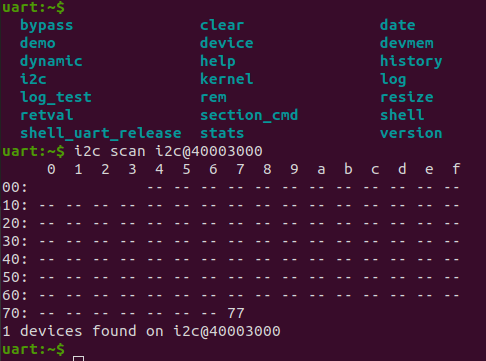

The Zephyr project supports a variety of Microcontroller boards, with different families (e.g: Cortex-M4, Risc-V) and vendors (STMicro, Nordic, NXP, Silabs, etc). To take a closer look at the level of support, we’ve chosen a set of boards with different vendors and families, and have tested different boards with various samples present in the SDK to determine which have out-of-the-box support:

| Board / OOTB Support | Hello World | Blinky (GPIO) | Echo Bot (UART) | Shell (I2C) |

| STM32G0 Nucleo (nucleo_g0b1re) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nordic nRF52840 Dev-kit (nrf52840dk) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| ESP32 WROOM (esp32_devkitc_wroom) | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Raspberry Pi Pico (rpi_pico) | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Silabs EFR32xG21 WSTK board (efr32_radio) | Y | N | Y | N |

Some observations:

- Building the boards is relatively consistent across targets: issue west build -b <board_target> <application>, which will build as long as the particular target has the hardware features required to run it.

- Flashing each target may be consistent, with some gotcha’s:

- If not debugging probes (an external J-Link or an on-board J-Link), “west flash” may not be supported. For instance, the RPi Pico comes with an UF2 bootloader and, to program the board, one needs to drag-and-drop the binary into the Mass Storage Device window.

- If the code built is a multi-application (e.g: Including MCUBoot in the build, or using TF-M), care needs to be taken to properly load each image in the correct sequence (potentially a manual process).

- The same is the case when using a board with a multi-core SOC (e.g: the nRF5340, with an application and a network cores).

- When working with different boards, do not assume that all the features are arranged to guarantee a unified user experience. For instance:

- RPi Pico:

- The I2C peripheral does not work right off the bat.

- The UART console is not mapped by default to the USB-micro port. One needs to declare a CDC ACM port in the device-tree (e.g: an overlay).

- ESP32-WROOM:

- Does not have an LED in the device-tree by default.

- EFR32MG21:

- It does not have I2C buses instantiated in the device-tree (this is also true for the other efr32_radio targets).

- The on-board LEDs are not mapped to the device-tree definition (this could be due to my board rev not being an exact match).

- RPi Pico:

Sensors Support

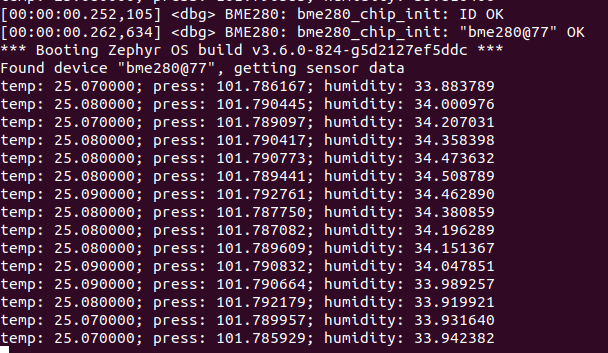

In this aspect, as well, Zephyr has an extensive list of sensors supported in-tree. All of these sensors follow a standard pattern, which after being instantiated in the device-tree (in the corresponding pattern node), then are exposed through a defined set of APIs, defined in zephyr/include/drivers/sensor.h.

The idiom for this API basically consists in two main operations: fetch() and get(). The fetch() API (sensor_sample_fetch) consists in polling the sensor values by physically interacting with the sensor itself (e.g: data registers being read through I2C or SPI) and store them in the driver. The get() API (sensor_channel_get) is simply getting and converting those results for the application usage.

The following snippet showcases this in a sample for the BME280:

int main(void)

{

const struct device *dev = get_bme280_device();

if (dev == NULL) {

return 0;

}

while (1) {

struct sensor_value temp, press, humidity;

sensor_sample_fetch(dev);

sensor_channel_get(dev, SENSOR_CHAN_AMBIENT_TEMP, &temp);

sensor_channel_get(dev, SENSOR_CHAN_PRESS, &press);

sensor_channel_get(dev, SENSOR_CHAN_HUMIDITY, &humidity);

printk("temp: %d.%06d; press: %d.%06d; humidity: %d.%06d\n",

temp.val1, temp.val2, press.val1, press.val2,

humidity.val1, humidity.val2);

k_sleep(K_MSEC(1000));

}

return 0;

}

Some thoughts around the Sensors Support:

- Defining APIs as generic as possible, and standardizing the sensor data units makes it very easy to use various sensors interchangeably, irrespective of the vendor (e.g: BME280 and SHTC3, sharing the same APIs to acquire temperature and humidity).

- Also, the concept of fetch() and get() is also very intuitive and easy to learn/use across different sensors.

- On the other hand, being generic implies that the level of granularity at which sensors can operate is somewhat limited. This means that it is not un-common to find yourself looking through the driver code and concluding that the mode you had envisioned for the sensor is not supported, and that the code needs to be reworked.

- Along the same lines, up until recently, using features such as a data-buffering FIFO would likely end up in using device-specific APIs, which defeat the purpose of the general standardized APIs.

Conclusions

- Zephyr has a strong foundation where a well-defined and consistent framework for developing hardware agnostic code is presented, clearly allowing swapping physical components with minimal modifications to applications.

- The balance between between functional granularity and re-usability of the existing APIs is still evolving and we should only expect more configurability and features across releases, as more components are introduced and standardized thorugh hierarchiccaly structured models, such as the sensors module.

- The ratio between variety of boards supported vs the quality of support still exhibits a high variability between vendors and families, with some community and vendors still to catch-up to the most supported ones. The determining factor here is the vendor involvement; and we’ve seen more silicon manufacturers joining the project. We should also expect significant improvement on this aspect as well in the upcoming releases.

You must be logged in to post a comment.